-

Submissions Information for Authors

This information is also available in PDF. The Harvard Negotiation Law Review invites the … Continue Reading

-

Articles

Check out articles from our most recent volumes below. … Continue Reading

SUBSCRIBE TODAY

Learn about how to subscribe to receive a copy of our journal.

MEET OUR EXECUTIVE BOARD

Learn about our executive board for the most recent HNLR Journal Volume.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Learn more about our upcoming events.

JOIN HNLR

Learn more about getting involved with HNLR.

About HNLR

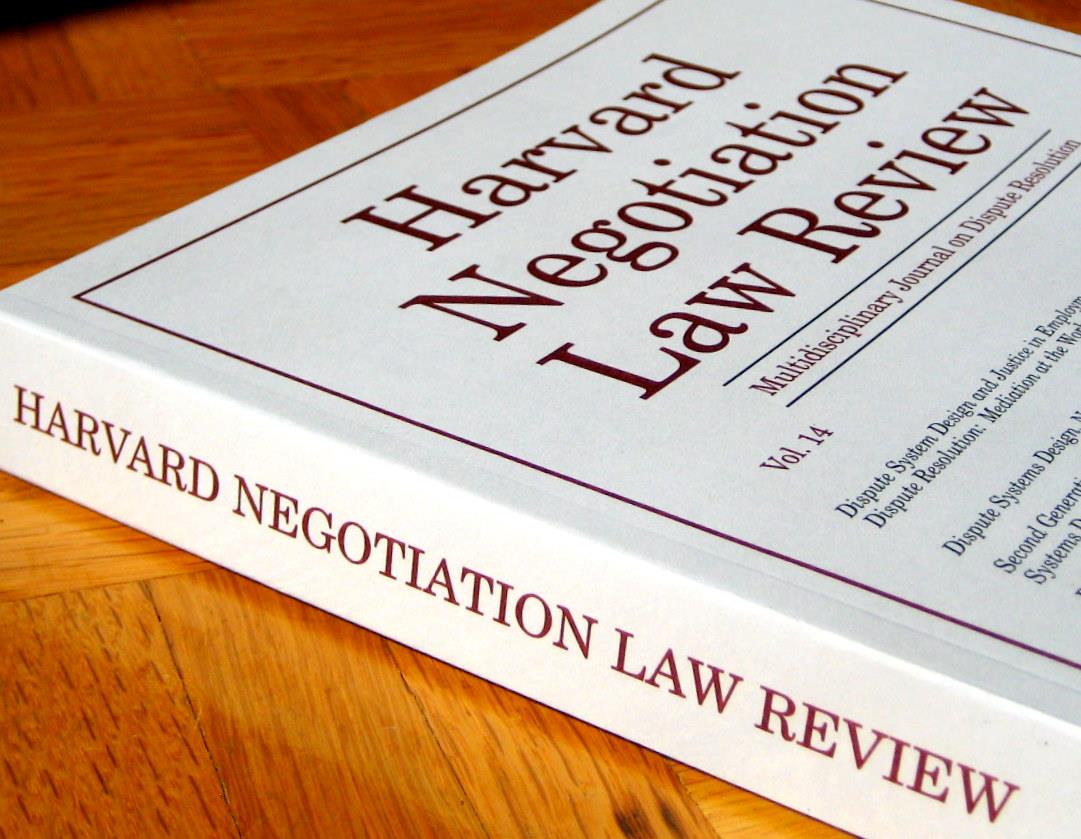

Negotiation, not adjudication, resolves most legal conflicts. However, despite the fact that dispute resolution is central to the practice of law and has become a “hot” topic in legal circles, a gap in the literature persists. “Legal negotiation” — negotiation with lawyers in the middle and legal institutions in the background — has escaped systematic analysis.

The Harvard Negotiation Law Review works to close this gap by providing a forum in which scholars from many disciplines can discuss negotiation as it relates to law and legal institutions. It is aimed specifically at lawyers and legal scholars.

OUR FLAGSHIP SPONSOR

Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School